Determining if there has been publication can mean looking at a

fine line

Copies of manuscripts are sometimes offered to friends, colleagues, professionals in the same field, yet such limited distribution does not usually amount to “publication.”

With motion pictures and television, a large number of strangers — potentially the

entire population of the United States — can be offered a chance to view a work, and

yet the courts have said this amounts to at most “limited publication” rather

than full-fledged publication as dealt with in some strict portions of the copyright laws.

Consider the following three continuums:

Continuum of publication for a motion picture:

|

Continuum of publication for a television work:

|

Continuum of publication for an artwork (painting, sculpture, etc.):

|

The preceding continuums were created by the copyrightdata.com editor. These

continuums do not have a parallel in the copyright statutes. Nonetheless, the

delineations drawn above are ones that are made in court decisions, in isolated passages

of the Copyright Act, and in the writing of a respected scholar of copyright law.

Interpreting the continuums:

The condition in the layer at the top of each of the

three continuums is a manifestation of indisputable publication. A creator whose

work has been distributed in the manner outlined must accept that his work has achieved

the legal threshold of publication, and such a creator or publisher must accept that he must

comply with any applicable registration requirements if copyright protection is to be accorded

by law. On the bottom layer of each of the three continuums is a condition which

is indisputably an instance of a work not published. In such cases, the creator has

always been protected by law (if not statutory law, it was common law), limited only by

time restrictions imposed in the 1976 Copyright Act which eliminated protection for works

still not published decades after the death of the creator.

In the middle layers of the continuums are various gradations between indisputable publication and indisputable lack of publication. Those closest to the extremes are really just slightly different manifestations of publication and lack of publication which are itemized here only so that readers here can better understand that these conditions are mere variations not worthy of special legal status.

Nearest to the center of each continuum are the indistinct “borderline” cases which have required learned specialists in copyright minutia to discern the legal status. Some of these conditions have resulted in verdicts that “limited publication” has taken place, with consequent carefully-structured decisions affecting the rights of copyright holders. Key court decisions in this area are summarized on the “limited publication” Citations and Case Summaries page of this web site.

Watch Out for Works Not Published Immediately

Knowing when a work was created is not enough to determine the expiration date of the copyright. For works first published in the United States before 1978, the term of copyright is determined by the date of publication, not the date of completion or of the creator’s death. (Works published after 1978 other than those copyrighted by corporations are granted a term of copyright lasting the lifetime of the author and a specific number of decades thereafter.) Because publication started the clock on a copyright in the 19th century, some works created during those one hundred years continue to enjoy copyright in the 21st century.

Emily Dickinson lived from December 10, 1830, to May 15, 1886, writing nearly eighteen hundred poems during her lifetime. However, only about a dozen of that large output were published while she was alive. A posthumous selection was published as a collection in 1890, and additional volumes were published during the 1890s. Starting in 1914 and continuing through the 1930s, a series of volumes was published, with many previously-unpublished poems going into print for the first time. As of year 2008, any work copyrighted 1923 or later still enjoys copyright (assuming compliance with requirements), so the combination of facts outlined here means that a poet who had been dead 37 years in 1923 was having works of hers start terms of copyright that would extend 95 years after that. Works published for the first time the following decade will be in copyright even further beyond Dickinson’s death. Had she lived more than a century later and had not published anything until 1978 or later, all of her works (whether or not published in her lifetime) would have copyright expire at the same time — ninety-five years after her death. Had she died a British citizen in late 1911, all of her works would have had copyrights lasting her lifetime and fifty years thereafter, and thus all would have expired at the same time. Because she was an American at a time when copyrights lasted a fixed, uniform period of time beyond publication, her works could remain in copyright a long time provided her heirs were willing to ration them, doling them out at intervals.

The saga of Dickinson’s copyrights doesn’t end with the series that went into the 1930s. In 1955, an edition was published of Dickinson’s poems that respected the stylized punctuation and capitalization of Dickinson’s originals, without the editing of earlier editions. As a result, aspects of the poems unique to the 1955 edition when Thomas H. Johnson published it may enjoy copyright further into the future than will the altered earlier versions.

Irving Berlin wrote “God Bless America” for his 1918 show Yip Yip Yaphank, but decided that its emotion did not fit the light patriot revue that his show was otherwise, so the song was removed. Any rehearsals the song may have had do not constitute publication, and the song was not that year performed for an audience let alone issued as sheet music or a recording. Twenty years later, the mood of the United States was different, and Irving Berlin then made it available to an American public eager to embrace the song on radio, in recordings, and as sheet music. The period during which the copyright holders (which no longer included Berlin once he donated his rights to charity) could reap financial rewards did not suffer for the twenty years during which the song languished in the composer’s possession; instead, the law as it existed at the time set the publication date as the beginning of the copyright term. (Put in other words: Berlin’s 1918 song has a copyright measured from 1938, because 1938 is when the song was first published.) The lengths of terms can be determined from the tables on the tree-view chart page. The tables are separated between published and unpublished works, and within tables by year of publication, lifetime of creator, and whether the copyright claimant is/are individual(s) or a corporation.

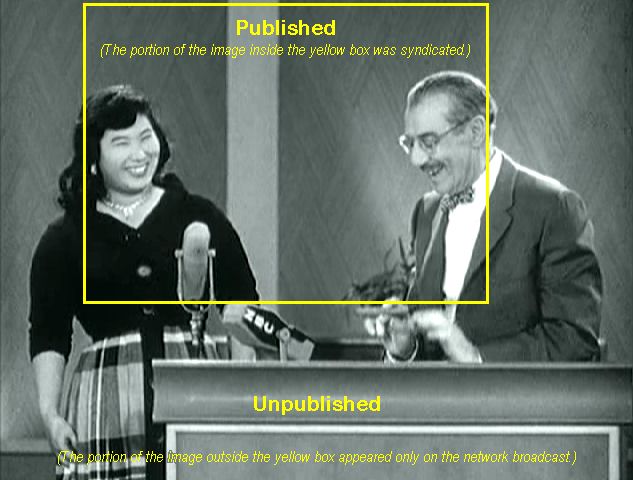

Illustrations: portraits of Irving Berlin which appeared on sheet music of his songs in (top) 1919 and (bottom) 1914.

|

Unpublished works are given a time limit on copyright eligibility

| “Works in existence but not published or copyrighted on January 1, 1978: Works that had been created before the current law came into effect but had neither been published nor registered for copyright before January 1, 1978, automatically are given federal copyright protection. The duration of copyright in these works will generally be computed in the same way as for new works: the life-plus-70 [for works copyrighted by individuals] or 95/120-year [for corporate works] terms will apply to them as well. However, all works in this category are guaranteed at least 25 years of statutory protection. The law specifies that in no case will copyright in a work of this sort expire before December 31, 2002, and if the work is published before that date the term will extend another 45 years, through the end of 2047.” (Information Circular 15a) |

| Why would it be necessary to guarantee that starting 1978

“in no case will copyright in a work of this sort expire before December 31,

2002”? A simple answer: There were works that had never been published which

were created by people who had been dead more than half a century. A follow-up

question: Why be concerned about works that no one was interested enough in publishing

even when the works were new and the authors able to promote the works? An

incredible answer: A valuable work could surface worthy of as much legal protection and

public attention as contemporary best-sellers. Congress didn’t foresee it in 1976, but in 1990 there was discovered in a forgotten trunk the long-missing half of the original manuscript of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. This literary classic was shorn of entire chapters prior to publication, and it was now possible to offer readers lengthy passages by the esteemed author which had never before been put into print. By beating the deadline of December 31, 2002, the expanded version of the book remains in copyright through the end of 2047. (The text as first published in 1885 remains in the public domain.) |  |